Who Decides What We Know?

Written by Baynes Courtney

I’m not a scientist or a historian. But I’m also not obligated to accept knowledge uncritically just because it’s labeled “mainstream.”

Much of what we’re taught about science and history was formalized by a narrow group of people during eras when racism, colonialism, and exclusion weren’t side issues. They were the structure. That doesn’t automatically make the knowledge false. But it does raise a fair question… how much was shaped by power, perspective, and self-interest?

Science is often presented as neutral. History as settled. Yet both are human processes. People decide what gets studied, what gets preserved, and what gets dismissed. When entire populations were locked out of institutions, their knowledge systems, oral histories, and interpretations were rarely treated as legitimate. They were often classified, reframed, or erased.

One of the most widely documented examples of science operating from a racist framework is the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service. For forty years, Black men with syphilis were deliberately left untreated without informed consent, even after penicillin became a known cure. This wasn’t fringe science. It was government sanctioned research, published and defended under the assumption that Black lives were expendable in the pursuit of knowledge. The failure wasn’t data. It was ethics shaped by racism.

Tuskegee shows how racism shaped scientific practice. What followed was the same logic hardened into law. One of the clearest examples of this appears in how race itself was legally defined. Under laws like the Virginia Racial Integrity Act of 1924, the state enforced a rigid racial binary that reclassified many Indigenous people as “colored,” based on government assumptions about Blackness rather than lived identity. The law didn’t discover ancestry. It imposed it.

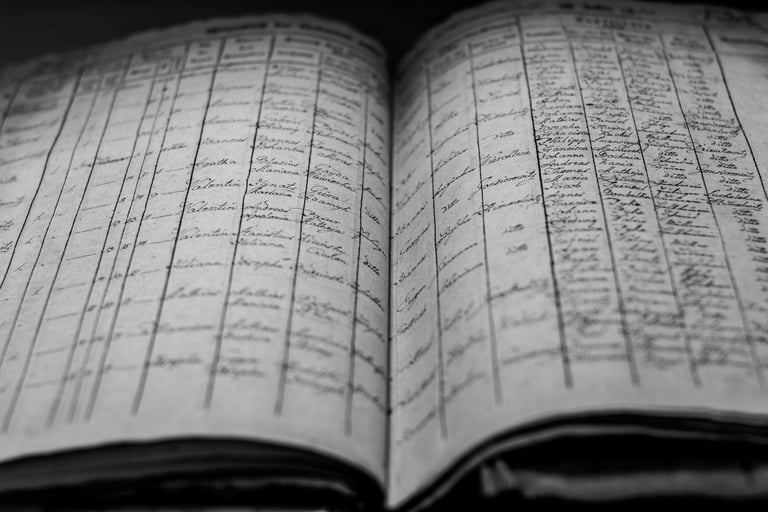

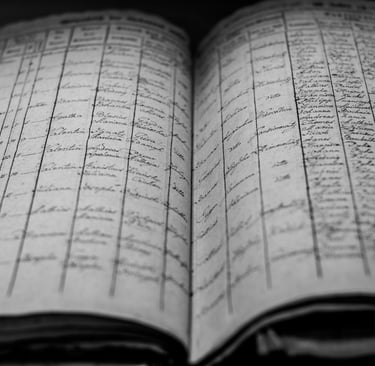

That system was enforced by people, most notably Walter Plecker, Virginia’s first registrar of vital statistics and a committed eugenicist. Plecker aggressively altered birth and marriage records, instructed clerks to eliminate “Indian” as a category, and worked to ensure that Indigenous people were legally erased on paper. Historian Arica L. Coleman has described this kind of record manipulation as “pencil genocide,” where identity was destroyed bureaucratically rather than biologically.

Growing up, I heard many Black families talk about Indigenous ancestry. I’ve seen Native communities whose appearance doesn’t match the narrow image most Americans have been taught to expect. I’ve reported on land being returned to Indigenous groups, only for outsiders to question their legitimacy based on how they looked. Those moments stayed with me because they revealed how deeply identity itself has been filtered through colonial definitions.

None of this is an argument to reject science or dismiss evidence. Genetics, in fact, has done more to dismantle racial hierarchy than support it. Findings from the Human Genome Project showed that all humans share more than 99.9% of their DNA, and that the greatest genetic diversity exists within African populations, not between so-called races. One of modern science’s most important contributions was confirming that race is not a biological boundary, but a social one.

Still, even scientific findings require interpretation. And interpretation is shaped by culture, language, and assumptions. For far too long, race was treated as biology, long after it should have been understood as a construct.

So the issue isn’t whether science is real. It’s whether our understanding of it has been unnecessarily narrow.

What if we treated mainstream knowledge as a starting point, not a finish line? What if independent, global coalitions of scientists and historians from diverse backgrounds were tasked not with overturning facts, but with revisiting conclusions, recontextualizing narratives, and reassessing what was excluded?

Not to replace one authority with another. But to balance the record.

Knowledge should evolve as participation widens. Truth doesn’t weaken when more voices examine it. It sharpens.

And if we’re confident in what we know, then expanding who gets to question it shouldn’t feel threatening. If it does, that alone tells us why reexamination matters.